Featured Image is Am Fronleichnamsmorgen, by Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller

No one is born an empiricist or a rationalist.

A newborn does not construct reality from first premises or observe a neutral array of objects which must be interpreted. A baby is born into a set of natural relations, especially with the parents and especially with the mother.

Babies don’t have language pressed on them; they instinctively seek it out. Once they find it, they begin soaking it up like a sponge.

Everyone, whether an infant, a child, a teenager, an adult, or the elderly, are thrown into a situation full of significance. Life resembles a game in which both the rules and the purpose are hinted at but never revealed. We encounter most objects in their perceived relation to the game of life. The scissors in our desk in elementary school are not just some meaningless matter; its shape and its location in our desk already hint that it has some specific purpose.

The reason that the rules and purpose of the game are never completely revealed is that they are influenced—I hesitate to go as far as to say “determined”—by the playing of the game itself.

A lot of the game is mere doing—actually using the scissors to cut paper, going to school, sitting at your desk. But a great deal of the game is telling, or saying, or listening—which of course is a kind of doing, but a very special kind.

A community is sustained by a conjective web of significances, including practices understood largely inarticulately, and narratives that give articulated (as well as implied) purposiveness to the world around us.

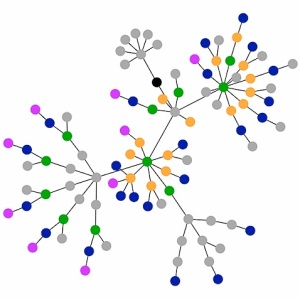

This web can be usefully thought of in terms of network clusters, rather than something uniform and discrete.

We play sub-games with subsets of the community which nevertheless have implications for the larger game of the community at large.

Sub-games and sub-communities are sources of experimentation with new ideas, rules, and practices. They are therefore the sources of both creativity and disorder for the community at large.

The moves we make can have very different significance depending on which game they’re interpreted as being a part of. A constructive move in a sub-game could be a destructive or counterproductive move if interpreted as a part of the larger game, or a different sub-game. The reverse is also possible.

The Revolt of the Public and the Crisis of Authority can be seen as arguing that our current overall situation pushes us to make moves that are considered constructive within our sub-games but are destructive in the larger game. But our current media environment has largely dissolved the walls between such games, so that they are carrying on as before but the moves can no longer be made within isolated sub-games. We tend to view this as good when the moves made by our ideological enemies in previously obscured sub-games are now observable to us, and vulnerable to attack. But the cumulative effect of everyone pursuing such a strategy is negation and nihilism.

Let’s hope that we’re able to adapt the game of life to our new information environment so that such a result is no longer fore-ordained.

Previous Posts in This Thread: